Alzheimer's disease, the most common form of dementia, affects millions of people worldwide. While memory loss is the hallmark symptom, scientists have long observed that subtle changes—like a reduced sense of smell—often appear years before cognitive decline becomes noticeable. Now, a groundbreaking study by a team of German researchers sheds light on why this happens, pinpointing an early degeneration in a small but critical brain region: the locus coeruleus.

Published in a leading neuroscience journal, the study titled "Early Locus Coeruleus Noradrenergic Axon Loss Drives Olfactory Dysfunction in Alzheimer's Disease" offers compelling evidence that damage to noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus may be one of the earliest neurological events in Alzheimer's progression—preceding even the buildup of amyloid plaques and tau tangles traditionally associated with the disease.

Olfactory dysfunction, or the impaired ability to detect and identify odors, is a well-documented early symptom of Alzheimer's. Many patients report difficulty smelling familiar scents like coffee, spices, or flowers long before they experience memory lapses. This isn't just anecdotal—clinical studies have shown that smell tests can predict future cognitive decline with surprising accuracy.

But why does the sense of smell go first? The answer may lie in the unique anatomy of the olfactory system. Unlike other sensory pathways, smell signals travel directly from the nose to the brain without passing through the thalamus. This direct route makes olfactory neurons particularly vulnerable to early neurodegenerative changes.

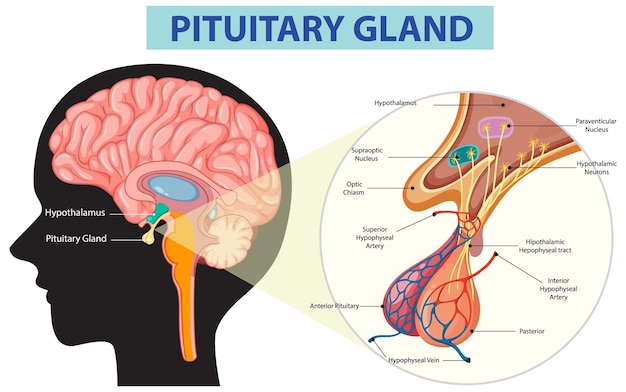

The locus coeruleus, a tiny nucleus located in the brainstem, is the primary source of norepinephrine (also known as noradrenaline) in the brain. This neurotransmitter plays a crucial role in attention, arousal, stress response, and memory. Importantly, the locus coeruleus sends noradrenergic axons—nerve fibers that release norepinephrine—to many brain regions, including those involved in olfactory processing.

The German research team used post-mortem brain tissue from individuals at various stages of Alzheimer's disease and employed advanced immunohistochemical techniques to map the integrity of noradrenergic axons. They discovered a significant and selective loss of these axons in the olfactory bulb and related cortical areas—occurring even in the earliest stages of the disease, before widespread cognitive symptoms emerged.

This finding suggests that the degeneration of the locus coeruleus isn't just a side effect of Alzheimer's—it may be a driving force behind early sensory deficits, particularly in smell.

The locus coeruleus is among the first brain regions to accumulate tau protein pathology, one of the key hallmarks of Alzheimer's. Its neurons have long, unmyelinated axons that extend throughout the brain, making them metabolically demanding and more susceptible to oxidative stress and inflammation.

Additionally, the locus coeruleus is highly responsive to environmental stressors such as toxins, infections, and psychological stress—all of which are being investigated as potential risk factors for Alzheimer's. Early damage to this region could disrupt norepinephrine signaling, impairing neural plasticity, increasing neuroinflammation, and accelerating the spread of pathological proteins.

The study's findings open new avenues for early diagnosis and intervention. If olfactory dysfunction is driven by locus coeruleus degeneration, then smell tests could serve as a simple, non-invasive screening tool to identify individuals at high risk for Alzheimer's—long before memory problems arise.

Moreover, preserving noradrenergic function could become a therapeutic target. Drugs that enhance norepinephrine signaling or protect locus coeruleus neurons might slow or even prevent the progression of early Alzheimer's pathology. Some existing medications, such as certain antidepressants and ADHD treatments, already modulate norepinephrine and could be repurposed for neuroprotective effects.

According to the World Health Organization, over 55 million people live with dementia worldwide, with Alzheimer's accounting for 60–70% of cases. With numbers expected to rise dramatically in the coming decades, early detection strategies are more critical than ever.

Raising awareness about early warning signs—like a diminishing sense of smell—can empower individuals to seek medical evaluation sooner. While not everyone with smell loss will develop Alzheimer's, persistent olfactory dysfunction warrants further investigation, especially in those with a family history or other risk factors.

The German study underscores the importance of looking beyond amyloid and tau when studying Alzheimer's. The locus coeruleus, once overlooked, is now emerging as a key player in the disease's earliest stages. Future research will likely focus on imaging techniques to monitor locus coeruleus integrity in living patients and clinical trials to test neuroprotective strategies targeting this system.

Understanding the sequence of events in Alzheimer's—from the first neuronal loss to full-blown dementia—is essential for developing effective treatments. This research brings us one step closer to detecting and intervening in the disease at its most treatable stage.

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Fitness

Health

Health