For decades, scientists have known that chronic stress is a major risk factor for depression. But the exact biological mechanisms linking psychological strain to mental health disorders have remained elusive. Now, groundbreaking research reveals a startling pathway: chronic stress causes immune cells called neutrophils to migrate from the bone marrow in the skull directly into the brain’s protective membranes, where they promote inflammation and contribute to depressive symptoms.

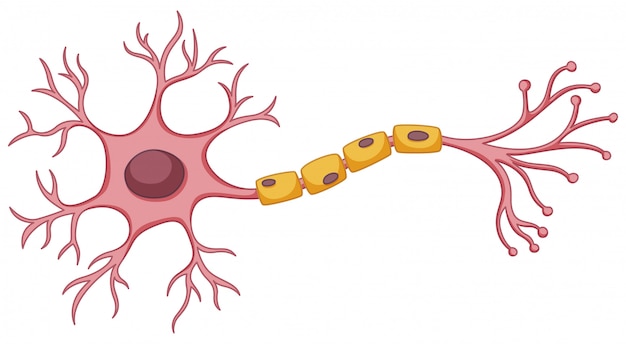

Unlike bone marrow in other parts of the body, the bone marrow in the skull has a unique and direct connection to the brain. This proximity allows immune cells to travel more efficiently to the central nervous system—especially under stress. The new study, conducted using advanced imaging and cellular tracking in animal models, found that prolonged stress activates the sympathetic nervous system, which in turn signals neutrophils in the skull’s bone marrow to mobilize.

These neutrophils don’t just enter the bloodstream—they move through microscopic channels in the skull bone and accumulate in the meninges, the layers of tissue that encase and protect the brain. Once there, they release inflammatory molecules that disrupt normal brain function.

Microscopic channels connect skull bone marrow to the brain’s protective layers.

Neutrophils are typically known as the body’s first line of defense against infection. They rush to sites of injury or pathogens, engulf harmful agents, and release chemicals to neutralize threats. However, when these cells are activated by non-infectious triggers—like psychological stress—their response can become harmful.

In the meninges, neutrophils trigger localized inflammation. This neuroinflammation interferes with neural circuits involved in mood regulation, particularly in regions like the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. Over time, this disruption manifests as symptoms commonly seen in depression: persistent sadness, fatigue, loss of interest, and cognitive difficulties.

The discovery highlights a previously underappreciated feedback loop. Chronic stress → activation of skull bone marrow → neutrophil migration → meningeal inflammation → altered brain function → depressive symptoms → increased stress perception. This cycle may explain why some individuals struggle to recover from depression even after removing external stressors—the biological imprint remains active.

Researchers also observed that animals with higher neutrophil infiltration in the meninges exhibited more pronounced behavioral changes, such as social withdrawal and reduced motivation in reward-based tasks—key indicators of depression-like states in preclinical models.

One of the most significant findings is the specificity of the skull’s bone marrow. While bone marrow in the tibia (shin bone) also produces neutrophils, those cells were far less likely to migrate to the brain under stress. The skull’s marrow appears uniquely tuned to respond to central nervous system threats—or, in this case, misdirected signals from chronic stress.

This suggests the skull may act as a specialized immune surveillance hub for the brain. While beneficial in fighting infections, this system can become maladaptive when chronically activated by psychological stressors, turning a protective mechanism into a source of pathology.

Neutrophils (highlighted in green) gather in the meninges under chronic stress.

This research opens new doors for treating stress-related mental health disorders. Current antidepressants primarily target neurotransmitters like serotonin and norepinephrine. However, this study suggests that anti-inflammatory therapies—particularly those that block neutrophil migration or activity—could offer a complementary approach.

Scientists are now exploring whether drugs that inhibit specific adhesion molecules or signaling pathways involved in neutrophil mobilization can reduce neuroinflammation and depressive symptoms. Additionally, non-pharmacological interventions such as mindfulness, exercise, and improved sleep hygiene—which are known to reduce systemic inflammation—may also help by dampening this immune response.

While this research is still in its early stages, it reinforces the importance of managing chronic stress—not just for mental well-being, but for physical brain health. The mind-body connection is not metaphorical; it’s cellular, molecular, and measurable.

Practical steps like setting boundaries, practicing relaxation techniques, seeking social support, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle may do more than improve mood—they may literally protect your brain from inflammatory damage.

Future studies will aim to confirm these findings in humans, using neuroimaging and cerebrospinal fluid analysis to detect neutrophil activity in the meninges. Researchers are also investigating whether this pathway plays a role in other neurological conditions, such as anxiety disorders, PTSD, and even neurodegenerative diseases.

For now, this discovery serves as a powerful reminder: stress is not just 'in your head'—it reshapes your biology from the inside out. And understanding that process is the first step toward healing.

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Fitness

Health

Health