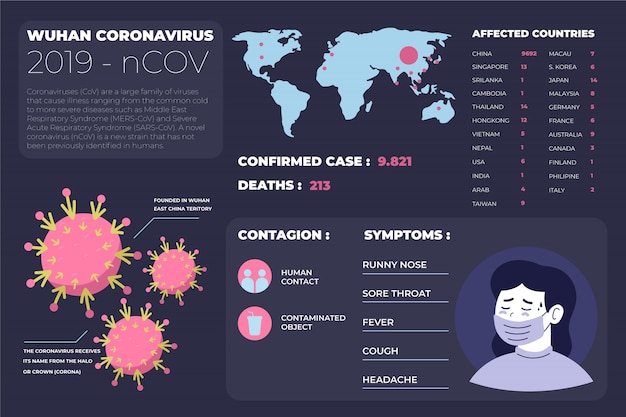

The highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1), commonly known as bird flu, has taken a concerning turn in the United States. Once primarily a threat to wild birds and poultry, the virus has now spread to dairy cattle—and even to humans. Since 2024, at least 70 people across multiple states have been diagnosed with the disease, marking a significant escalation in the outbreak’s reach and potential public health impact.

The bird flu outbreak began in wild bird populations and quickly spread to commercial poultry farms, leading to the culling of millions of birds to contain the virus. However, in early 2024, health officials detected the virus in dairy cows for the first time. This development raised alarms among scientists and agricultural experts, as it signaled the virus was adapting to new mammalian hosts.

California, the nation’s largest milk producer, has been particularly hard hit. Dairy farmers reported cows with reduced milk production, lethargy, and fever—symptoms later linked to H5N1. Despite biosecurity measures, the virus spread rapidly across herds, prompting emergency responses from federal and state agencies.

Monitoring dairy herds for signs of bird flu has become a new reality for U.S. farmers.

With the virus now circulating in livestock, human infections have followed. As of mid-2025, at least 70 cases have been confirmed across eight states. Most of those infected were farmworkers or individuals with direct exposure to sick animals. Symptoms have ranged from mild—such as cough, fever, and fatigue—to more severe respiratory illness in a few isolated cases.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) emphasizes that there is no evidence of sustained human-to-human transmission. However, each infection increases the risk of the virus mutating into a form that could spread more easily among people—a scenario that could trigger a pandemic.

In a troubling development, a cat in San Francisco was euthanized after contracting H5N1 from eating raw pet food contaminated with the virus. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning and recall for the brand—RAWR Raw Cat Food Chicken Eats—highlighting a new transmission pathway for the virus.

This case underscores the importance of pet food safety and the potential for the virus to jump between species through indirect exposure. Veterinarians now advise pet owners to avoid feeding raw poultry products and to monitor pets for respiratory or neurological symptoms.

A San Francisco cat became the first known pet to die from bird flu linked to raw pet food.

Federal agencies, including the USDA, CDC, and FDA, are working together to monitor the outbreak, support affected farms, and prevent further spillover. Measures include:

Despite these efforts, challenges remain. Many dairy farmers report frustration over unclear guidelines and delays in testing. The economic impact on the dairy industry—already under pressure—has been significant.

For most Americans, the immediate risk remains low. However, health officials recommend the following precautions:

The spread of bird flu to dairy cows and humans is a stark reminder of how interconnected animal, environmental, and human health truly are. While the current outbreak has not yet led to widespread human transmission, each new case increases the chances of a more dangerous mutation.

Investing in early detection, improving biosecurity on farms, and accelerating vaccine development are critical steps to prevent future outbreaks. As the virus continues to evolve, so must our preparedness.

The bird flu situation is fluid and evolving. Staying informed and taking sensible precautions can help protect both people and animals in the months ahead.

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Fitness

Health

Health