Industrial food production has transformed how we eat. It has made food cheaper, more abundant, and widely available across the globe. But this convenience comes at a cost. As ultra-processed foods dominate supermarket shelves and supply chains prioritize profit over nutrition, growing evidence points to serious health, environmental, and ethical consequences. The challenge now is clear: the worst excesses of industrial food production must be reined in—without compromising access to adequate calories for a growing global population.

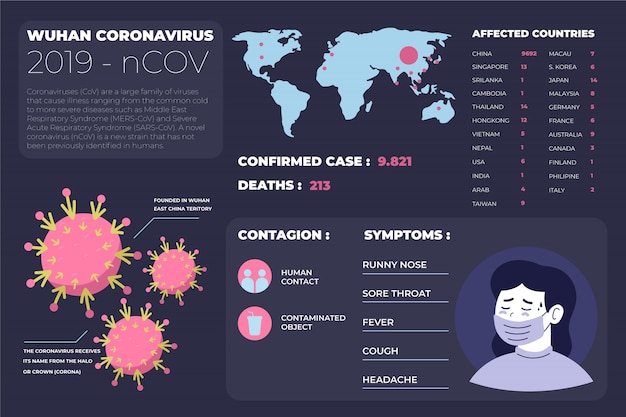

Over the past half-century, diets in many countries have shifted dramatically toward ultra-processed foods—items high in added sugars, unhealthy fats, salt, and artificial ingredients, while low in essential nutrients. These products, engineered for long shelf life and addictive taste, now make up more than half of the average diet in some high-income nations.

While they deliver calories efficiently, they often fail to provide balanced nutrition. Studies link high consumption of ultra-processed foods to increased risks of obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and even certain cancers. The convenience of these foods masks a deeper public health crisis, especially in low-income communities where nutritious options are less accessible.

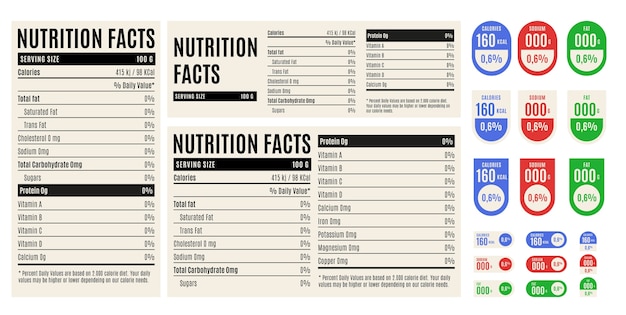

Common ultra-processed foods dominate modern diets, often at the expense of whole, nutrient-dense options.

The environmental toll of industrial food systems is equally concerning. Large-scale monocultures, heavy pesticide use, and intensive livestock operations contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, water pollution, and biodiversity loss. The drive for efficiency often sacrifices soil health and long-term agricultural sustainability.

Ethically, labor conditions in some industrial food supply chains raise red flags—from underpaid farm workers to unsafe processing environments. Animal welfare in concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) also remains a growing concern for consumers and advocacy groups.

Despite these issues, industrial food production plays a vital role in feeding billions. In many regions, especially urban areas and food-insecure communities, mass-produced foods are the most affordable and accessible source of calories. Eliminating them entirely would risk worsening hunger and malnutrition.

The key is not to reject industrial food systems outright, but to reform them. We must distinguish between necessary food production at scale and the harmful overreach of profit-driven, nutritionally poor products. Ensuring access to adequate calories cannot come at the expense of long-term health and planetary well-being.

Not all processed foods are harmful. Minimally processed items like frozen vegetables, canned beans, or whole-grain breads can be part of a healthy diet. The problem lies in ultra-processing—where foods are stripped of fiber and nutrients, then rebuilt with additives to enhance flavor, texture, and shelf life.

Experts are calling for a clearer, more scientifically grounded definition of ultra-processed foods to guide regulation and consumer awareness. Improved labeling, such as front-of-package warning systems used in countries like Chile and Uruguay, can help people make informed choices.

Clear labeling helps consumers identify ultra-processed foods and make healthier choices.

Governments, food producers, and public health organizations all have roles to play. Policies such as taxing sugary drinks, subsidizing fruits and vegetables, and restricting marketing of unhealthy foods to children have shown promise in shifting consumption patterns.

At the same time, innovation in food technology offers alternatives. Plant-based proteins, lab-grown meats, and nutrient-fortified staples can provide sustainable, scalable sources of nutrition without the environmental and health downsides of current industrial models.

Ultimately, the goal is to build food systems that are not only efficient but also equitable and health-promoting. This means investing in local agriculture, supporting small-scale farmers, improving food literacy, and ensuring that nutritious food is affordable and accessible to all—regardless of income or geography.

Urban farming, community-supported agriculture, and school meal programs are examples of initiatives that bridge the gap between industrial efficiency and nutritional quality. When combined with smart regulation and consumer education, they can help reshape the food landscape.

Sustainable farming practices support both food security and environmental health.

The industrial food system is neither entirely good nor entirely bad—it is a tool, shaped by economic, political, and cultural forces. To protect public health and the planet, we must rein in its worst excesses: the overproduction of nutritionally void, environmentally damaging, and ethically questionable foods.

At the same time, we must preserve—and improve—its ability to deliver sufficient calories to a world where food insecurity remains a pressing issue. The future of food lies not in rejection, but in reform: smarter production, better policies, and a renewed commitment to nutrition, equity, and sustainability.

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Fitness

Health

Health