For decades, beta blockers have been a cornerstone of post-heart attack care. Prescribed to millions worldwide, these medications were believed to significantly reduce the risk of future cardiovascular events. However, emerging research is challenging this long-standing medical practice, raising critical questions about their universal use—especially in patients with preserved heart function and among women.

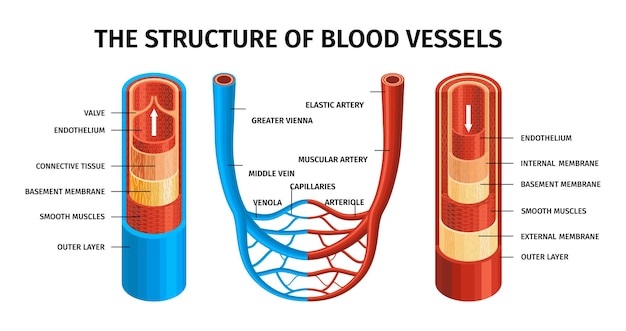

Beta blockers, also known as beta-adrenergic blocking agents, are a class of drugs that reduce the workload on the heart by blocking the effects of adrenaline. They slow the heart rate, lower blood pressure, and decrease the force of heart contractions. Since the 1960s, they’ve been widely used to treat conditions like high blood pressure, arrhythmias, angina, and heart failure.

Following a heart attack, beta blockers have traditionally been prescribed to improve survival rates by preventing further cardiac stress and reducing the likelihood of another event. For years, this approach was supported by clinical guidelines and considered standard of care.

Recent large-scale studies are now calling into question the blanket use of beta blockers after a heart attack—particularly for patients whose heart function remains normal or only mildly impaired. One major trial found that long-term use of beta blockers did not significantly improve cardiovascular outcomes in individuals with preserved ejection fraction, a measure of how well the heart pumps blood.

Even more concerning, some data suggest that in certain populations—especially women—beta blockers may not only be ineffective but potentially harmful. Subgroup analyses indicate that female heart attack survivors with normal heart function might face an increased risk of adverse cardiac events when taking these medications long-term.

Historically, cardiovascular research has been male-dominated, leading to treatment guidelines that may not fully account for sex-based differences in heart disease. Emerging evidence shows that women often present with different symptoms and pathophysiology after a heart attack.

In one study, women with preserved heart function who took beta blockers post-heart attack showed a higher incidence of heart-related complications compared to those not on the medication. Researchers speculate that the drugs’ effects on heart rate and blood pressure may disrupt normal compensatory mechanisms more significantly in women.

This doesn’t mean beta blockers are dangerous for all women—but it does highlight the need for personalized treatment plans based on individual risk factors, heart function, and sex-specific responses.

It’s important to emphasize that beta blockers are not obsolete. Patients with reduced ejection fraction—those whose hearts have been significantly weakened by a heart attack—still derive clear survival benefits from these medications. Clinical trials continue to support their use in individuals with heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction.

The shift lies in moving away from one-size-fits-all prescribing. Doctors are now encouraged to assess each patient’s heart function through imaging tests like echocardiograms before deciding on long-term beta blocker therapy.

These findings underscore a broader trend in medicine: the move toward precision healthcare. Rather than applying broad guidelines to all patients, clinicians are increasingly using diagnostic tools and biomarkers to tailor treatments to individual needs.

For heart attack survivors, this means evaluating not just the event itself, but the underlying condition of the heart, the presence of other risk factors like diabetes or hypertension, and demographic variables such as age and sex.

Shared decision-making between patients and providers is becoming more crucial. Patients should feel empowered to ask: Do I really need this medication long-term? What are the risks and benefits based on my specific condition?

If you’re currently taking a beta blocker after a heart attack, do not stop the medication abruptly. Sudden discontinuation can lead to dangerous spikes in blood pressure or even trigger another cardiac event.

Instead, discuss your treatment plan with your healthcare provider. Ask whether your heart function has been assessed, how much benefit you’re likely to gain from continued use, and whether alternative strategies—such as lifestyle changes, other medications, or closer monitoring—might be appropriate.

As research evolves, so too must clinical practice. The goal is not to discard beta blockers, but to use them more wisely. Future guidelines may recommend a more selective approach, reserving long-term therapy for those who truly benefit while sparing others from unnecessary side effects.

Ongoing studies are exploring genetic, hormonal, and metabolic factors that influence drug response, which could further refine treatment decisions in the years ahead.

The message is clear: when it comes to heart health, personalized care is the new standard.

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Fitness

Health

Health