For decades, scientists have warned that excessive alcohol consumption harms the liver. From fatty liver to cirrhosis, the consequences are well-documented. But a groundbreaking new study has uncovered a previously unknown mechanism—one that reveals how alcohol doesn’t just directly damage the liver, but also triggers a dangerous chain reaction involving gut bacteria that worsens the harm.

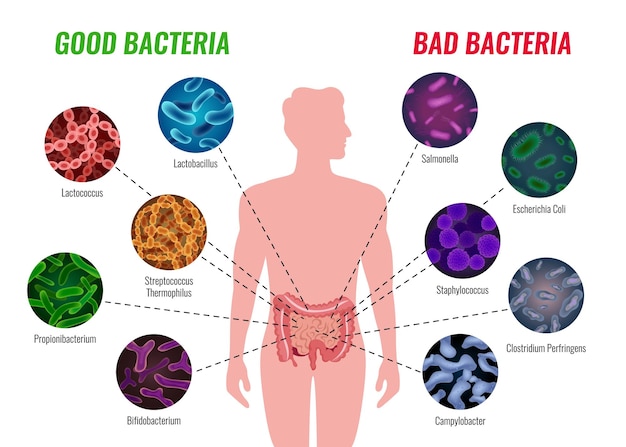

Researchers have discovered that heavy alcohol use disrupts the balance of gut microbiota—the trillions of bacteria living in our intestines. This imbalance, known as dysbiosis, leads to the overgrowth of harmful bacteria that produce toxic byproducts. One of these byproducts, endotoxin, leaks through the intestinal wall into the bloodstream—a condition called 'leaky gut.'

Once in circulation, endotoxins travel directly to the liver via the portal vein. The liver, already stressed by metabolizing alcohol, now faces a second assault. Immune cells in the liver respond to the endotoxins by triggering inflammation, which further damages liver tissue and accelerates the progression of alcoholic liver disease (ALD).

The study also found that alcohol interferes with a critical protein-recycling enzyme in liver cells. This enzyme, responsible for clearing damaged proteins, becomes less effective under chronic alcohol exposure. As a result, toxic proteins accumulate inside liver cells, impairing their function and promoting fat buildup—leading to alcoholic fatty liver disease.

This fat accumulation makes the liver more vulnerable to inflammation and scarring. Combined with the influx of gut-derived toxins, it creates a self-reinforcing loop: more damage leads to more inflammation, which worsens gut permeability, allowing even more toxins to flood the liver.

While the findings paint a concerning picture, there is hope. Another recent study highlighted that lifestyle factors like diet and physical activity can significantly reduce the risk of alcohol-related liver damage. Participants who maintained a high-quality diet rich in antioxidants, fiber, and healthy fats—and who exercised regularly—showed markedly better liver health, even with moderate alcohol consumption.

Foods such as tomatoes, which contain the antioxidant lycopene, and beverages like coffee have been associated with protective effects on the liver. These components may help reduce oxidative stress and inflammation, potentially interrupting the damaging cycle triggered by alcohol.

The urgency of these discoveries is underscored by recent trends. Alcohol use increased significantly during the pandemic, and rates of alcohol-related liver disease and deaths have continued to rise. In animal studies, binge drinking led to nearly 50% higher levels of liver triglycerides—indicating rapid fat accumulation—compared to abstinent subjects.

This surge highlights the need for greater public awareness and preventive strategies. Understanding the biological mechanisms behind liver damage empowers individuals to make informed choices about drinking and lifestyle.

The good news is that the liver has a remarkable ability to regenerate—if given the chance. Early-stage damage, such as fatty liver, can often be reversed through abstinence, improved nutrition, and increased physical activity. Medical support, including monitoring and targeted therapies, can further aid recovery.

However, once scarring (fibrosis) or cirrhosis sets in, the damage becomes largely irreversible. This underscores the importance of early intervention and lifestyle modification before serious harm occurs.

The new research illuminates a hidden danger: alcohol doesn’t act alone. It sets off a chain reaction that pulls gut bacteria into a destructive partnership with the liver. But by understanding this cycle, we gain power to break it—through smarter choices, healthier habits, and greater awareness of what truly happens inside our bodies when we drink.

Health

Health

Health

Health

Health

Fitness

Health

Health